The tyranny of the supertweeter

Twitter shows us a skewed version of the world, but it's not necessarily because of the algorithm.

You've heard it before: Twitter Is Not Real Life. This is supposed to induce you to pause your doomscroll and go play outside. It's an admonishment that implies that there is something about the site itself that drives people mad: get off Twitter, if you can manage it, and you can return to being your calm, normal self. Being on Twitter certainly produces a kind of feeling — the sense of being at the mercy of a vast, unruly crowd, constantly stumbling into conversations that are variously brilliant, insipid, hilarious, violent, enlightening, and disturbing.

A few years ago, we heard a lot about "filter bubbles." Were Americans becoming polarized because social media platforms fed them a steady drip feed of content algorithmically tailored to keep them online by provoking an emotional response? Well, maybe. But timeline-based social media doesn't need to deploy any particular algorithm to create an unbalanced picture of the world.

The reason is simple: in a big crowd, some people simply talk more. On Twitter, you don't see people; you see tweets. Since people with different opinions tweet at systematically different rates, the picture at the tweet level is even more skewed than Twitter's usership. Select a random American and you're about as likely to get a Democrat as a Republican. Select a random tweet and it's not unlikely that you're peering into the mind of a lunatic.

Start with the obvious: Twitter is not real life in the same way that college is not real life: most people don't go, and those who do attend are not representative of the population at large. Twitter users are whiter, more well-off, and more highly educated. Like college students, they lean left. But Twitter's user base is not representative of what you see when looking at a sample of tweets.

The data

Pew tells us most of what we know about Twitter's demographics. But information about political opinions—and weird attitudes — we can get via the American National Election Studies, which are conducted around the time of every US presidential election. Here, we'll be using ANES 2020, which was conducted before the election. This is pretty recent — it's anyone's guess how much more or less sane Twitter has gotten since then.

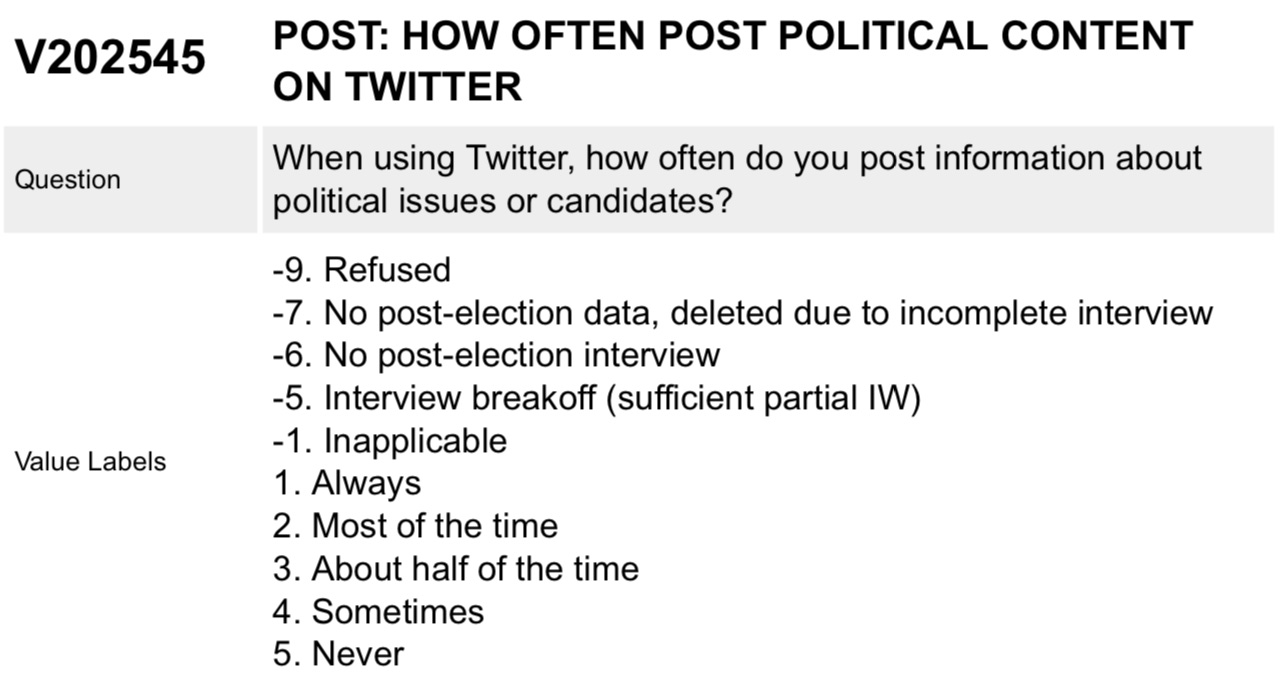

ANES is a nationally representative survey that asks respondents questions about their political beliefs, their demographic characteristics, their voting habits, and — most importantly for our purposes — their media consumption. Interviewers administering the ANES in recent years have asked respondents about which social media sites they use, how often they look at them, and even how often they post:

This allows us to separate the set of ANES responses into two groups:

Twitter users

Normal people

Pew tells us that Twitter users are more likely to have gone to college, but doesn't tell us how likely college grads are to use Twitter. ANES tells us: about 64% more likely. ANES also asks users (1) how often they use Twitter and (2) how often they post political content when they do use Twitter.

The rough figures given in the answers to these questions allows us to try to estimate roughly how much people are posting. For more information on the analytical choices allowing us to do this, you can check out the page for this article on GitHub

Political bias on Twitter

Using ANES to compare Twitter to the population at large, it's easy to see that political moderates are underrepresented on Twitter. Relative to the population at large, people who identify as either liberal or conservative are overrepresented. Fine: perhaps people on Twitter are simply more politically aware. The platform allows you to express any opinion you want, so it probably attracts people who have one.

The more interesting part comes when we use the "how often do you use/post" questions to ask not what the distribution of users looks like, but what the distribution of tweets looks like:

Though only around 30% of Twitter users identify as "Liberal" or "Extremely liberal", those users are evidently responsible for around 60% of tweets. This is "posting bias" — Twitter's user base has a certain character, but the tendency to tweet is not evenly distributed across that population. So while Twitter's user base has a moderate liberal bias, a random selection of tweets has considerably more liberal skew.

Emotional bias on Twitter

If you have ever felt that Twitter has a negative atmosphere, you are not alone. And now you can prove it. The designers of ANES were kind enough to include a number of questions that are not explicitly political but instead try to get at people's feelings and attitudes about the world.

Twitter users are generally only slightly more irritated, outraged, hopeless, or violent than nonusers. But the tendency of these particularly unhappy users to post more frequently means that they are overrepresented at the tweet level: though only about 1 in 10 non-tweeting Americans believes that political violence is sometimes justified, the number of Tweets coming from someone with that attitude is closer to 1 in 4. Evidently only half of nonusers are super-outraged; at the tweet level, extreme outrage is more of a 4-in-5 kind of deal.

The point

Of course, few people are seeing a random selection of tweets. Twitter users curate their timelines, and the algorithm — opaque as ever — makes secret choices about what to show them and what not to. But posting bias remains, even within whatever online bubble we've managed to knit together for ourselves.

The data we see here tell us that, at the platform level, tweets by politically liberal and/or miserable people are overrepresented relative to the prevalence of those attitudes in the general population. But we're looking under the lamppost. There are a lot of things that might be related to someone's tendency to tweet, and most of them aren't asked about in political opinion surveys.

What kinds of qualities could be positively correlated with the tendency to tweet more? The desire to be perceived positively by others seems like a good bet: in the form of the Like button, Twitter offers an easy way for people seeking mass approval to shoot their shot. Indeed, Twitter allows them to shoot as many shots as they want.

It's just as easy to imagine the reverse being true. If you like seeing people lose their minds over a joke or a very spicy take, then there's very little chance you're not a frequent tweeter; the pickings are too ripe. To the extent that pure trollery constitutes a personality trait, we are probably comfortable in assuming that it is dramatically overrepresented on Twitter.

Who cares?

Only about a quarter of Americans use Twitter. But among the many weird things about the platform is its importance to various small and insular subsets of the population. For certain professions, Twitter is about as real as life gets. It's how they network with colleagues, find jobs, get the news, dig up inside information, and make like-minded friends.

Journalists are one such group. According to a recent Pew poll, nearly 70% of them say Twitter is central to their work. The number is even higher (83%) for journalists under 29. The very cacophony that makes Twitter feel insane is what makes it so useful to journalists: finding a great source for a story is as easy as finding the right combination of search terms. It is a utility now as indispensable as the steno pad once was. What journalist in their right mind (and willing to sacrifice it) would refuse to use Twitter?

Twitter is also evidently important for Congressional staff. Thanks to other polling, we know that two-thirds of Congressional staffers spend at least thirty minutes a day on Twitter. A majority say that the Senator or member of Congress they work for uses it themselves.

We don't know who else in a position of influence is relying on Twitter for ideas... though there's some evidence that Jay Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, may consult it for ideas on monetary policy.

Posting bias on Twitter means that discourse there will influence the communities where it is important in unpredictable ways. Twitter's leftward slant, for instance, doesn't necessarily mean that it will pull users left; it could just as easily provoke a reaction across the aisle. Though "defund the police" was never a popular slogan in mainstream electoral politics, it got a lot of play on Twitter, generating a reaction among conservative journalists and policy aides who spend an inordinate amount of time on the platform.

In some communities, it might be positive personality traits that dominate: among some circles of academics, for instance, a desire to share knowledge altruistically might mean that users sharing useful or novel findings are responsible for a larger share of tweets.

Really, though, only one thing is for sure, and that's that Twitter Is Not Real Life.

This article proves Twitter is real life. The main people that use it are the politicians, journalists, academics and educated people. To me that fits the 80/20 rule. Thats the 20 percent of the population that influences and controls this world.

Great post!!! Loved the data-centric approach!